The 1916 Soldiers’ Riot

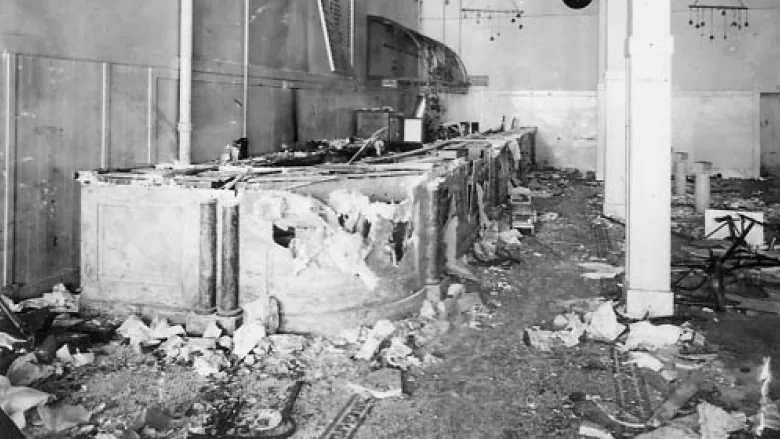

Photo by Glenbow Archives

The White Lunch restaurant occupied the ground floor of the building at 128 8th Ave S.E., (where the Calgary TELUS Convention Centre stands now) with a second location at 108 9th Ave S.W. (near what is currently Banker’s Hall)

It was a popular lunch diner with the soldiers encamped in Calgary waiting to move on to training in Valcartier, PQ before embarking overseas to fight in the trenches of France and Flanders. The restaurant’s manager, Frank H. Nagel, was friendly with a number of soldiers.

However, in early February of 1916, a rumour started that Nagel had let go of two returning veterans who had been employed at the restaurant and replaced them with two immigrants from German and Austria.

What had actually occurred was an employee of the restaurant had quit to enlist in the army, but was discharged due to being unfit. He was given his job back by Nagel but fired at a later date because he refused to wash the floors. His replacement was from Austria.

When he heard the nature of the rumour going around, Nagel was sufficiently concerned to request help from local military officials to quash the dangerous gossip. But it was already too late.

On the night of Feb. 10, 1916, a mob of 500 uniformed soldiers, some of whom were drunk, attacked both locations of the White Lunch, as well as the McLennan Dancing Academy above the 8th Ave site.

The Calgary City Police and the Calgary Fire Department responded before the looting began, but the Calgary Police were outnumbered by the mob.

Chief Constable Alfred Cuddy lined up his available officers, 15 in total, in front of the restaurant and asked the soldiers to leave, but a stone thrown through the front window of the restaurant incited violence.

Cuddy was concerned any force used by the police would further antagonize the soldiers and people would be injured or killed. It was not until General Cruikshank, the CO of Military District 13, arrived that the mob disbursed.

Assistant Fire Chief Alexander “Sandy” Carr informed him of the events.

The five police officers sent to protect the 9th Ave location were also unable to stop the looting for the same reason.

Nagel, his wife, and Fanny Applebaum, a cashier, were both at the 8th Ave location at the time the mob arrived. Nagel attempted to talk to the crowd, but could not make himself heard over the jeering and yelling. When the looting began, both women were allowed to leave the building unmolested.

Damages to the White Lunch locations were estimated at $25,000 to $30,000 (approx. $640,000 to $767,000 in current dollars). The dance studio had its piano smashed, while chairs were thrown out the windows. Damage was estimated at $1,000 (approx. $2,500 in current dollars).

The following day, a second mob of 1,500 soldiers formed and crossed the Langevin (now the Reconciliation) Bridge to loot the Riverside Hotel.

A rumour had circulated that the German owner of the restaurant had hosted pro-German meetings at the establishment, including a celebration of the burning of the parliament buildings on Feb. 3, 1916.

The riot carried on for two hours, with alcohol stolen and every room of the hotel destroyed. The mob was eventually dispersed by the military, as the police were again outnumbered and concerned about inciting more violence.

While the former owner of the hotel was Charles Poffenroth, the current owner was Alfred E. Ebbsworth of Blackie, a British immigrant who leased the hotel to John Rioux, a French-Canadian. The area of Calgary where the hotel was located was known as Germantown, its inhabitants were mainly German-speakers from Russia, an ally of Britain and France.

Damage at the Riverside Hotel was estimated to have been around $10,000 (approx. $256,000 in 2022 dollars).

Mobs also gathered around the Kolb’s Restaurant, Cronn’s Café, the Calgary Furniture store, and the Palliser Hotel, but guards protected these locations.

The attacks were reported across Canada, including Ottawa, and discussed in the House of Commons, which pressured local military authorities to respond.

A handful of soldiers were charged for the Riverside Hotel attack and military authorities in Calgary forbade soldiers from going to local bars. They also assured the Federal Government that tighter restrictions would be brought about to prevent any more outbreaks of “anti-German excitement”. Armed military guards were posted at the City Hall, the Palliser Hotel, and the brewery to prevent any more attacks.

The city council addressed the violence as well, voting 9-0 to fire any ‘enemy aliens’ working for the City and replace them with soldiers returning from the war. Mayor Costello went so far as to advise employers to let any German or Austrian staff go to protect their property.

Chief Constable Cuddy would later hypothesise that the attacks were planned by a German or Austrian, who enraged both soldiers and civilians. He noted that no properties owned by Germans or Austrians had been attacked.

Several soldiers were charged in light of the attacks and were represented in court by local lawyers.

Private D.J. McDonald, represented by John McKinley Cameron, was charged with taking part in a riot and destruction of property in reference to the White Lunch restaurant attacks. He was found guilty and fined $50 or 60 days in jail.

Private George Stevenson was charged in the attack on the White Lunch restaurant and was represented by Barney Collison and Mark B. Peacock. He was found guilty and fined $50 or 60 days in jail.

Private Gottfried Kraft of the 89th Battalion was a Russian German. He was charged with throwing the rock through the front window of the White Lunch restaurant, the catalyst that started the looting. Kraft enlisted on Nov. 15, 1915, and sailed on the S.S. Olympic on May 31, 1916.

While serving in France, Kraft would receive a bayonet wound to his left arm on Aug. 18, 1917, and fractured his left hand on June 15, 1918. Kraft survived the war and returned to Calgary when demobilized on May 30, 1919, farming in the Eckville district until his death on April 17, 1943, at the age of 49.

Private Harry Hughson, a member of the 89th Battalion, was accused of stealing one bottle each of rye, champagne, and beer from the Riverside Hotel. Hughson was an electrician by trade when he enlisted on November 15, 1915. He was serving with the 31st Battalion when he was killed in action on September 25, 1916, during the Somme Offensive.

Private Edward Heil of the 56th Battalion was arrested for stealing liquor from the Riverside Hotel. In his defence, Heil pleaded not guilty, saying the alcohol was given to him by another soldier, who asked him to hold it until the soldier could return.

Heil was found guilty. Heil enlisted on Nov. 18, 1915, in Calgary, where he was working as a baker. Heil sailed on the S.S. Baltic on March 20, 1916, and served in France. He was admitted to the hospital with pyrexia of unknown origin (a fever for which a cause cannot be determined), on July 25, 1917, and was released to return to his unit on Aug. 4, 1917.

On Aug. 11, 1917, he was absent from roll call but returned shortly afterwards and was fined three days’ pay. Heil went absent without leave again on March 16, 1919, for five hours, for which he forfeited 21 days’ pay. April 25, 1919, he was sentenced to seven days in the stockade for going to town without a pass and getting drunk. Heil was discharged in Vancouver on July 14, 1919

Private J. Benner of the 56th Battalion was also charged with taking part in a riot and pleaded not guilty. It was not reported as to the outcome of his trial.