The town that changed Alberta

Photo by Glenbow Archive

The small town of Turner Valley, just 63 kilometres southwest of Calgary, has a history steeped in the petroleum industry, with the development of Canada’s first commercial oilfield that triggered Alberta’s first oil boom in 1914.

This is a historical look at how it all happened:

William Stewart Herron has been referred to as the “Father of Alberta’s Petroleum Industry.” Herron was an Ontario native who spent time in the Pennsylvania oilfields. In 1905, he and his wife relocated to Alberta and bought a ranch in the Okotoks area. To supplement the ranch income, he started a freight and cartage business, mainly hauling wagonloads of coal from Black Diamond, which he sold to area ranchers and people in Okotoks. In the spring of 1911, while he was waiting for coal to be loaded, he noticed a natural gas seep coming from the banks of Sheep River. He scooped up the bubbling substance into jars and sent the specimens to the University of Pennsylvania. Results confirmed the material was “wet natural gas” which is natural gas with a high concentration of liquid naphtha. After confirming the quality of the gas, he hastily purchased thousands of acres of property including surface and mineral rights.

In July 1912, Herron recruited Archibald Wayne Dingman for his drilling expertise. Dingman was entrepreneurial-minded and as early as the 1890’s he was invested in office and apartment buildings, commuter railways and streetcar lines. He had worked in the Pennsylvania oilfields and had been involved in drilling a gas well in Edmonton. Dingman had moved to Calgary in 1906 and along with partners formed Calgary Natural Gas Company, which extracted gas from wells on the Sarcee Reserve. Dingman engaged several investors, including A.E. Cross, Senator James Lougheed and Richard B. Bennett, to incorporate Calgary Petroleum Products.

On May 14, 1914 they struck petroleum at 2,718 ft, sending a gusher into the air. The well was named Dingman #1.

“Oil Fever”

When Dingman #1 blew, “oil fever” swept through Calgary. Stories of the discovery dominated the following day’s front page of The Calgary Daily Herald. Herron and Dingman entertained hordes of people that rushed to the site in cars and horse-drawn wagons to see the well.

The Duke of Connaught – Prince Arthur, the third son of Queen Victoria, was Governor General of Canada. He and his wife, Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia insisted on seeing Turner Valley during their visit to Alberta in September of 1914. At 2:31 pm, driller Marty Hovis opened the valve and the well erupted and the volatile gasoline fluid shot up into the air. The valve was closed at 2.34 pm and the princess, reportedly, rushed forward to dip her white glove into the fluid.

The discovery at Turner Valley was significant not only because it was the first major strike in western Canada but also because it was the first major oil discovery in Canada in 50 years. The economic activity spurred the establishment of the Calgary Stock Exchange. Within a few months of the Dingman strike, more than 500 companies were formed. More than $1 million was withdrawn from Calgary banks to be invested in drilling companies. Of the hundreds of companies formed, only 50 drilled while few actually found oil. Most who invested in Turner Valley oil speculation lost their money.

A fire in 1920 destroyed many of the buildings at the Turner Valley plant and represented the end of the first phase of Turner Valley operations. It also forced Calgary Petroleum Products’ to sell the facility to the Royalite Oil Company, a subsidiary of Imperial Oil. It was Royalite that ushered in the second boom period of Turner Valley.

Samuel G. Coultis was the first person hired by the newly formed Royalite Oil Company. He had a degree in chemical engineering and had gained experience in the oil industry working for the Alberta Southern Refining Company for which he developed a type of still for producing gasoline, kerosene and two kinds of distillate. Coultis was entrusted with the design of a new gas processing plant to replace the Calgary Petroleum Products plant that had burnt down. Besides, a new absorption plant was built to strip gasoline from the wet gas, as well as a compression plant that pressurized the gas for transmission. He established Madison Laboratory which supported all aspects of Royalite’s activities.

The company succeeded in getting an agreement with Canadian Western Natural Gas (CWNG) to allow its pipelines to be used to transport natural gas from Turner Valley to Calgary. Royalite built a connector pipeline from the Turner Valley plant to Okotoks and ultimately to CWNG Bow Island-to-Calgary pipeline. For the first time, Turner Valley natural gas was able to reach a large consumer base. The compression plant doubled in size in 1923.

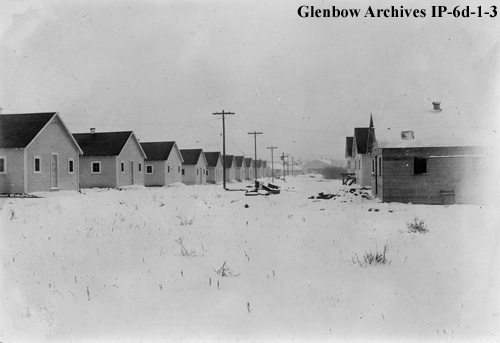

The growth and activity in the area created an immediate and urgent need for housing in Turner Valley area. There were virtually no existing options available in the early 1920s. Royalite built several bunkhouses for single men, near the plant known as “the Batch”. Other companies established camps for workers which offered the bare minimum necessary for housing – single rooms, communal showers and a cookhouse serving meals round the clock. The high demand for housing presented economic opportunities for entrepreneurs in both Turner Valley and Black Diamond who opened boarding houses and multi-purpose buildings that offered accommodation to workers. The most notable of these was a two-storey structure built around 1926 and known locally as the Log Cabin. It became one of the social hubs at the Turner Valley townsite.

Most of these housing options were temporary and many workers and their families wanted more substantial housing. Mobility was essential for workers and so small shacks, typically 12 by 24 were built on skids to allow them to be moved. A much more stable and comfortable form of housing took root among the managers, scientists and other professionals. A planned neighbourhood, on a hill, across the Sheep River, was established in 1921 by Royalite, and the unofficial name was Snob Hill, which hints at the class divisions present at the time. The name has stuck throughout the years and there are twenty of those original homes, most since remodeled, on Royalite Way. The writer of this article lives in one of those original houses, next door to where Samuel Coultis and his family lived.

A new drilling program

Royalite embarked on a new drilling program in September 1923 when drilling began on the Royalite # 4 well (Dingman wells #1, 2 and 3 had been renamed Royalite #1, 2 and 3). By spring 1924, the well’s pressure fell dramatically so drilling began again but reached harder limestone at 3450 ft when they were ordered to stop drilling. The team, however, ignored the order and continued to drill and at 3750ft the drill bit became stuck. On October 14th, while attempting to retrieve the drill bit, the well blew in at a rate of 20 million cubic feet of natural gas a day. The gas ignited on October 19th destroying the derrick. The glow from the blaze could be seen as far away as Lethbridge. The fire raged for weeks before a team of experts from Oklahoma used to steam and dynamite to extinguish the flames and prevent it from re-igniting.

Once the fire was extinguished, Royalite had to deal with the gas. Royalite #4 was the first sour gas well in Alberta. Hydrogen sulfide, identifiable by its rotten egg smell, is unstable, corrosive and explosive. To produce safe, useable products the hydrogen sulfide has to be removed in a process called sweetening. Coultis was responsible to address this problem and in 1925 created a scrubbing operation at Turner Valley similar to a plant/process used by Union Gas Company in Ontario. The increased production of gas at the plant exceeded existing pipeline and trucking capacity. The excess was piped into a ravine and burned in a common practice known as flaring. As the flare roared and burned bright day and night, the area became known as Hell’s Half Acre.

The increased production of gas exceeded existing pipeline and trucking capacity, causing Royalite to begin building several new pipelines to the Imperial Oil refinery in Calgary. By 1928, production increased to 60 million cubic feet of gas per day. Royalite’s success and profitability enabled it to begin acquiring competing companies in the area. Many smaller companies, lacking their own transportation networks and refining facilities, were forced to rely upon Royalite’s pipelines and Imperial Oil’s refinery, further entrenching Royalite and Imperial Oil in Alberta’s developing oil and gas sector.

The crash of the U.S. stock market in October 1929, rocked the world and led to The Great Depression. In Alberta, it hit at the same time wheat prices were tumbling. Samuel Coultis used his position as manager to order food at the company’s expense for distribution to local residents throughout The Great Depression. While he was questioned on this practice by company officials, he was never asked to stop.

In the 1930s, the flaring of gas created a serious problem for Royalite. Years of uncontrolled flaring of natural gas had resulted in a drop in pressure throughout the Turner Valley field making it more difficult to bring oil to the surface.

In 1933. Royalite opened the first Canadian high-pressure lean oil facility. The next major discovery, known as Turner Valley Royalties #1 began producing oil in 1936. This new well was not a Royalite or Imperial Oil well and it was primarily an oil rather than gas well. This led to the third boom in the area triggering a drilling boom at the south end of the oilfield.

At its peak during WWII the Turner Valley oilfield produced about 10 million barrels of oil per year.

Although it was aging, the Turner Valley Gas Plant operated until 1985, nearly 70 years after it was first built.

In 1989 the Turner Valley Gas Plant was designated a Provincial Historic Resource and in 1995 it was proclaimed a National Historic Site of Canada.

This article highlights the early years in the petroleum industry in Alberta and the importance of the Turner Valley discovery. For anyone interested in the additional history of the Turner Valley Gas Plant, the Turner Valley Oilfield Society is a great resource. This site includes videos and information on tours, unfortunately now suspended due to COVID-19.